Semi-Coherent Strands of Thought and Tech Experiments

What I think about and do when I have time.

Design Jiu Jitsu

—

Four days a week I walk two blocks from my house to the Theodorou Academy of Jiu Jitsu where I get kicked, punched, choked, thrown, and have my limbs hyper-extended. I’m very bad at it, but I enjoy the process of learning something new, especially something that is so embodied.

Every month or so, the Boston Public Library has a book sale. The books are very cheap and you can find some hidden gems if you know where to look. Well, I found something of the holy grail in the jiu jitsu/judo community: a first edition of Kyufo Mifune’s The Canon of Judo. At the time, I had some ideas percolating in my head. Ideas about learning, about time-taking, about how jiu jitsu, the ‘gentle art,’ teaches you how to deal with resistance. The Canon of Judo clarified these ideas into something coherent — a way to think about problems in design through the lens of jiu jitsu (I’m using jiu jitsu and judo here interchangeably, you can ask me later about the historical reason for doing so).

In design work and in jiu jitsu you deal quite prominently with three types of resistance: physical resistance, the need to improvise, and ambiguity. So I gave a talk and led an exercise in how we might reframe the way we think about resistance through thinking about productively reframing it as something to work with rather than against.

My three examples were the tunneling of the Thames — how two different engineering teams worked with the unique kind of resistance of the mud and tidal pressures of the river, the parks Aldo Van Eyck designed in Amsterdam post-WW2 to teach children how to navigate unfamiliar spaces, and the history of New York City’s tenement stoops — how residents reclaimed them for purposes other than their original intention.

In the studio, I later ran a session to test out these ideas with IDEOers. We set the rules that each team had to make letterforms using either cement blocks (physical resistance), flowers (improvisation), or the environment around them (ambiguity). The results and the methods by which everyone arrived at their final letters were beautiful.

Wrestling and Storytelling

—

Where I currently live, Watertown, MA, has a robust amateur professional wrestling scene. These shows are about $5 to attend and, for my money, these guys are as good as anything you see on TV. I love going to them, and have won over many a skeptic. There’s only so much cynicism you can hold in your heart before you see a guy jump off the ropes, do a perfect flip like Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, before smashing another guy through a table and into the center of the Earth.

However, as a writer, I can’t help but notice the storytelling devices the wrestlers use to get the crowd hooked. So I went to a match, and then presented my findings back to the IDEO community about what wrestling can teach us about telling a good story.

For example, the Heel. The guy we love to hate. But also, usually, the most interesting character. When William Blake read Milton’s Paradise Lost, a text meant to “justify the ways of God to men,” he was confused. Why did he give Satan all of the best lines? The heel at this show was a guy named Mecca. His main villainousness is that he’s from Philadelphia. He called everyone in the crowd “buck-toothed hillbillies” and then said he hoped everyone’s car gets broken into as he strutted away with the title belt. I booed. I booed so much. I loved it.

Some of the other topics covered were Chekhov’s Gun (if you’re going to throw thumbtacks in the ring, you better use them), misdirection, and how to build towards a satisfying finale.

A Drive-By Lullaby

—

I am slowly but surely churning out a novel. It’s called A Drive-By Lullaby. I imagine it’ll take me a few years to finish, but it’s my favorite thing to do. I want to combine the hardboiled detective novel a la Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett with the picaresque novel a la Mark Twain and Charles Portis.

So, naturally, it’s about a guy who needs money, gets caught up in a financial scandal while investigating the disappearance of billionaire who has joined an undefined art cult in Upstate New York. It combines all of my favorite things — archeological crimes, professional wrestling, judo, department stores, the Hudson valley, the mythos of the American past, double-crosses, rogue burnouts, and potentially life-changing encounters with art.

It’s my attempt to think through a question that’s vexed me for my whole adult life: how can you reinvigorate the sensation of living again? Or, a bit differently: how do you see the world as if for the first time?

My Intern

—

For about a year I had my intern, Dr. Hollywood, posted (literally) outside my office. He wasn’t very useful except for standing in for me during meetings I didn’t have time to attend. I’m not sure how convincing of a replica he was, but I never received any complaints.

However, on special nights, when the moon is big and heavy and the mood is right and the drinks are flowing, he will come alive and DJ. I can’t explain it. Some things are neither true nor false. They just are.

Learning From Constraints

—

I hosted a workshop at our IDEO Cambridge studio about whether art is just decoration, or if it teaches us something new. Also, and this is something we take for granted, why write something like a poem at all? Surely there are more straightforward ways to get your point across.

At one point in my life I was an aspiring / fledgling academic, and these were the questions I wanted to explore. What do these strange things we call “artworks” do, and why does every culture have some form of extremely strict poetic structure (we covered everything from Icelandic to Welsh to Japanese verse).

The short version of my argument is this: we become habituated to the world around us. The more our lives become routine, the less we notice about them. Our minds are meant to economize. Our perceptual worlds get less rich the more we go through the motions. This is easy to imagine. Think of the first time you saw something striking, maybe it was the view of a waterfall from a park bench. You visit the waterfall everyday and now, maybe after a few weeks, do you still notice the view? Does it contain the perceptual richness of the first time you saw it?

Art exists in a different register than our normal, routinized lives. It speaks oddly; it refers to things in oblique ways; it depicts things with unusual techniques. It estranges us from our habitual mode of seeing things. By struggling through a poem, maybe one like William Carlos William’s Paterson which depicts a waterfall, we are forced to make new connections, to see the waterfall through a different light. So that when we go back to sit down on the park bench, some of that perceptual richness is restored.

I chose poetry because I like literature, but the point remains the same. When we sit down to do something like write a poem, and we have to forgo our normal, straightforward way of speaking by doing something like rhyming or counting syllables, we need to describe whatever it is we’re talking about in a way that uncovers some new connection, some new knowledge. The mark of a good poet is that these connections aren’t arbitrary. That, holding an idea in suspension while searching for a certain resonance of sound, you arrive at something that tells you something novel about the world by being forced to speak about it differently than your habitual way of speaking.

To test whether a poem can teach us about an experience no one has ever had, I tried an experiment called “Can a poem teach us what it’s like to die?” using Emily Dickinson’s “I Heard a Fly Buzz” and John Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale” as our example. You can reach out to me for more detail about that discussion, but it revolved around the concept of “losing” oneself in sound!

Hot Talk LLC

—

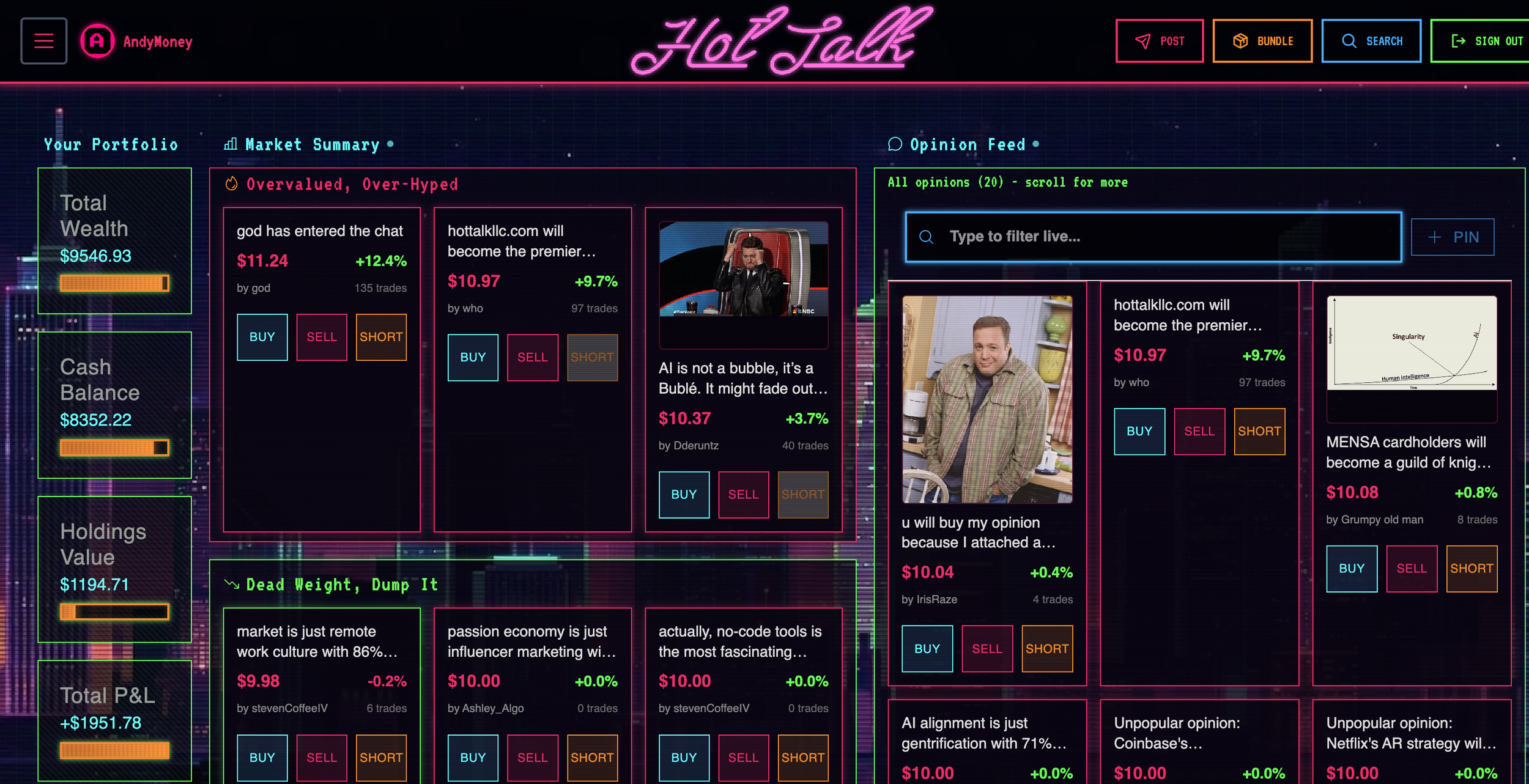

I created a prediction market. It was something I had been thinking about for a long time, at least since 2021 when I read the book Speculative Communities and realized how fundamentally our lives are dictated by the logic of speculation.

But where the traditional prediction market requires an outcome (ie, “The Seahawks beat the Rams”), I wanted to offer something different. A literal manifestation of The Marketplace of Ideas and a Keynesian beauty contest. You buy shares of a post, its value goes up; you sell shares, it’s value goes down. You can short a post, create bundles, and bet against or with an entire user’s portfolio.

You buy early, other people hop on, and then you cash out. It has stronger anti-arbitrage rules than the actual US securities trade laws.

The UX and brand is still a bit of a work in progress so as not to be so neon arcade hellscape, but it works. I used Realtime Database as my backend architecture and a mixture of React, Node.JS, and Vercel to code the platform.

It combines the discursive and speculative economies into something that’s gamefied, competitive, and could change how we engage with ideas online.

Doctor-Patient Simulator

—

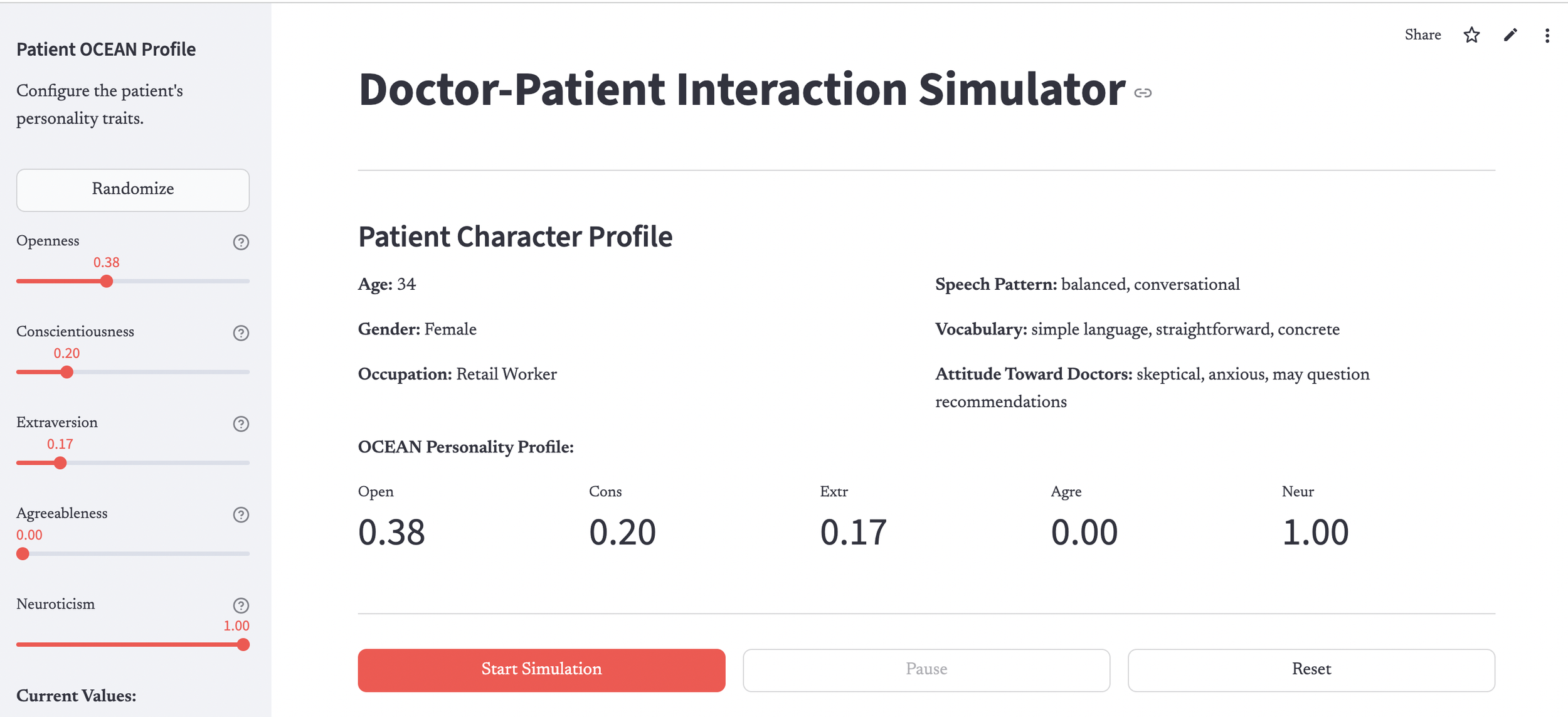

After working on a number of healthcare projects for IDEO, I started to notice a theme. Patients were feeling that their doctors weren’t listening, or were callous in the way they listened, while doctors felt that they didn’t have the time to actually speak to patients in a way that felt humane.

So I started running experiments with Python notebooks to see how I might simulate interactions between different types of doctors and patients, and then to analyze and benchmark their respective sentiment swings throughout. I wanted to know what type of sentences would cause a patient to feel worse, and what kind would make them feel better.

I coded it in Python and then passed it through Streamlit to give it a very simple UX. And then I allowed users to change the patient and providers’ OCEAN scores and the reason for visit. The conversation runs, and then it is benchmarked against the medically-recognized standards of excellence in patient communications. The major movers of sentiment are stored in the “Mood Impact Library,” and you can re-visit these over multiple simulations.

It’s by no means a polished project, and there’s much more I’d like to do with it (like fix some bugs), but it’s been an interesting illustration into how we can make that very fraught 9ish minutes they get with a patient.